Can Vietnam Meet the Moment?

As global firms pivot from China, Hanoi navigates ambition and bureaucracy.

Note: This piece was originally intended for the University of Kansas Trade War Lab, where I lead our communications team. If you enjoy my work, or want to know more about trade politics, I’d encourage you to subscribe to our Substack!

When Tim Cook landed in Hanoi in April of last year, the mood was celebratory. For years, Apple had relied on a vast, finely tuned supply chain embedded in China, its economic elder to thYe east. That investment helped transform China’s economic landscape, drawing in waves of foreign capital and creating hundreds of thousands of jobs. But Cook, whose rise to CEO was shaped by his mastery of supply chain logistics, was in Vietnam for a reason. Beyond sipping egg coffee and posing for photos with local fans in Hanoi, the visit signaled a broader strategic shift: Vietnam, not China, is now being cast as the potential next great industrial partner for companies eager to de-risk in the face of deteriorating U.S.–China ties. For Hanoi, the chance to replicate China’s FDI-driven transformation is without precedent. The question is whether it can move fast enough to attract and sustain the attention of high-profile executives and revenue-rich firms like Apple.

Talk of Vietnam as the next hub for American investment predates the current diversion between Washington and Beijing. President Obama lauded “the skyscrapers and high-rises of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City,” linking Vietnam’s growth story to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Although President Trump would withdraw from the TPP on his first day in office, he, too, courted Hanoi—hosting the second U.S.–North Korea summit there in 2019. President Biden, ever interested in expanding the traditional diplomatic might of America, reclassified the relationship between the two countries to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, paving the way for increased American investment in Vietnam’s burgeoning tech sector.

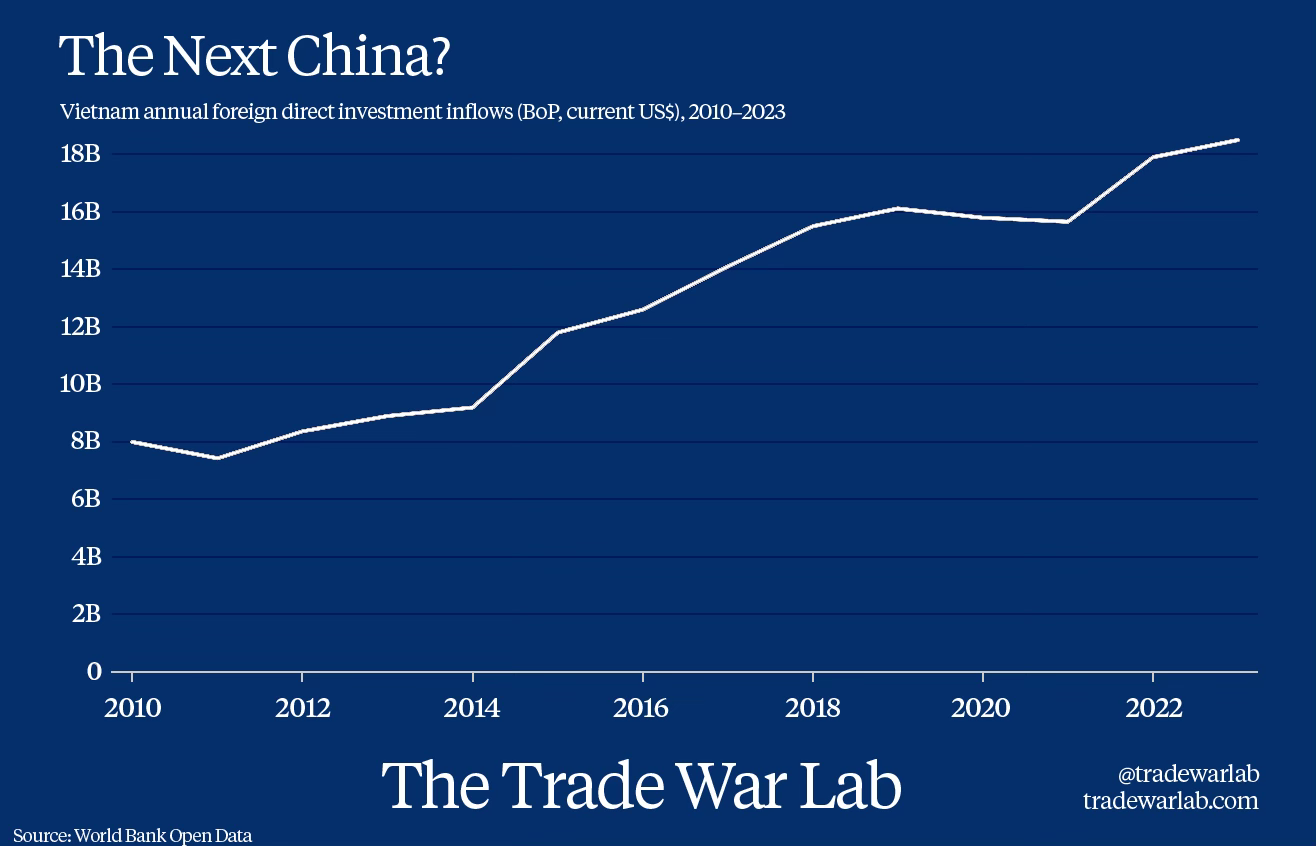

For American officials across administrations, Vietnam offers familiar allure: a young workforce (nearly 70% of the population is of working age), a median income still below China’s, and a reformist trajectory that, on paper, echoes the early days of China’s boom. Since 2010, FDI has surged nearly 70%, drawing in the likes of Intel and Coca-Cola. But while Vietnam courts foreign capital, its approval process remains cumbersome, saddled by ownership caps and opaque administrative hurdles. Vietnam holds no formal national security review, relying on the Communist Party’s authority to ensure risk and security. The Department of Planning and Investment (DPI) works as the first of a long bureaucratic chain; a reminder that the investment attraction of today is still not fully embraced by the political elite. The perpetual cautiousness endemic to the authoritarian state still holds restrictions for foreign enterprises, an environment some have argued is not dissimilar to the same Chinese foreign investment laws that Western companies and governments have grown uncomfortable with.

In order to unlock this economic dream, though, Vietnam must work to fix its infrastructure, which has been plagued by dated and decaying bridges, roads, and ports. The country has already forfeited over 2.5 billion dollars as a casualty to Vietnamese officials fearful of violating strict and broad anti-grafting laws, delaying infrastructure upgrades further out of sight. Domestically, the government has become mired in similar bureaucratic delays, failing to invest a quarter of its own public funds on infrastructure from 2021 to 2023. Unlike China, whose economic comeuppance was unique in both the scale of its population and the delay in allowing foreign investors access to its markets, Vietnam now has to compete with a host of other countries looking to gain off of China’s loss. India, which has also become central to Apple’s iPhone production, has worked to roll back restrictive labor and land acquisition laws in an attempt to court the same market that Vietnam looks to for its economic future. Another competitor, Malaysia, has established tax-free special interest zonesand worked to bring tech giants like Google and Microsoft to house their cloud infrastructure.

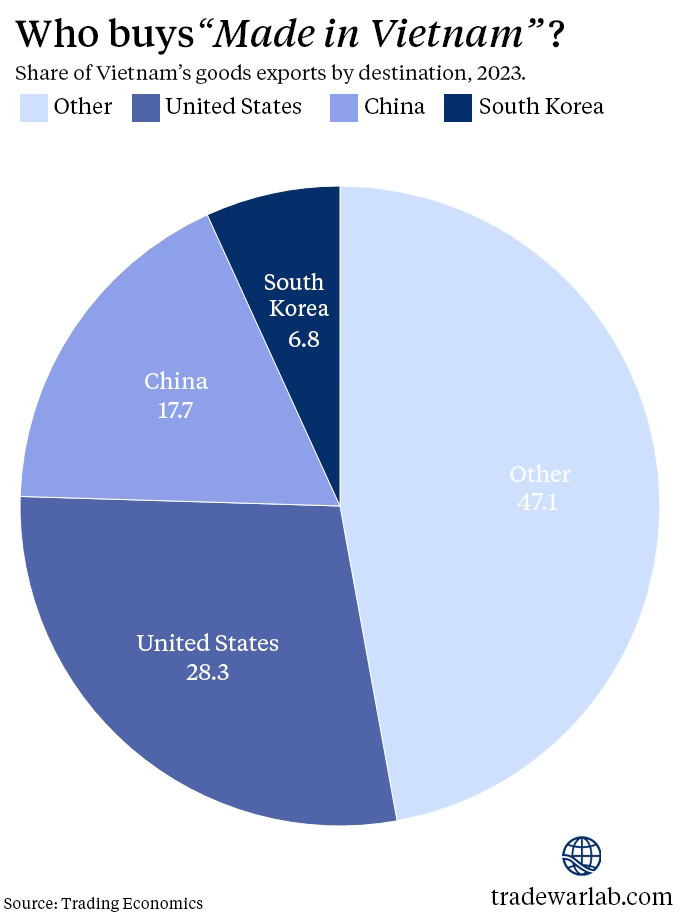

Despite hopes from American officials that increased trade could sway Hanoi away from Beijing and toward Washington,the country has remained steadfastly uninterested in picking a side. Pragmatism, not shared dreams of a socialist future, has defined Vietnam’s working relationship with China as the two countries have deepened their relationship. Trade with China now makes up nearly a third of total trade, up nearly fifteen percent from the previous year and cementing two decades of China being Vietnam’s largest import partner. President Xi Jinping has sought to bring Vietnam into a larger coalition against what he describes as “unilateral bullying” emanating from President Trump’s widespread “retaliatory tariffs.”

Those tariffs, which when initially announced promised to decimate Vietnam’s trade relationship with the United States through an astounding 46% tariff on imports. Vietnamese steel products are already hit with more than a four hundred percent markup, an industry that President Trump has long considered core to revitalizing American manufacturing. Attempts to placate President Trump from Hanoi, including facilitating the deportation of Vietnamese nationals and opening its market to Trump-favorite Elon Musk’s Starlink, have still failed to result in a new comprehensive trade deal before the ninety-day tariff suspension ends. While the President and his advisors had boasted of a slew of trade deals that would mend political and economic fences, the administration has secured just one deal so far, with the United Kingdom. For Vietnam, the threat of losing the United States, their largest single export destination, could erase their economic ascent and serve to heighten reliance on Chinese markets.

Tim Cook’s visit may have lasted only a few days, but for a country whose economic future is tied to the global trade order, the sense of both promise and uncertainty is equally strong. Vietnam will have to play politics in a way that China, whose accession to the World Trade Organization was shepherded by the United States, will not. The authoritarian state still has to bring economic vitality to placate the younger and more pragmatic generation of Vietnamese who have grown up in an era of internet access and in a country still reeling from the devastating war less than half a century ago. As the Gulfstream G650, Cook’s private jet of choice, took off from Noi Bai International Airport, few could have expected what would come of the global trade system that could both give and take away the future of a hundred million Vietnamese.