Fermis & Filters

At what point do we stop going all the way, and why?

The Fermi Paradox attempts to explain one of our species’ greatest mysteries: the very nature of our cosmically isolated existence. With over two trillion galaxies in the observable universe, the handicaps to life are not rooted in statistics. How, then, do you explain a universe seemingly teeming with hosts for life but lacking life itself?

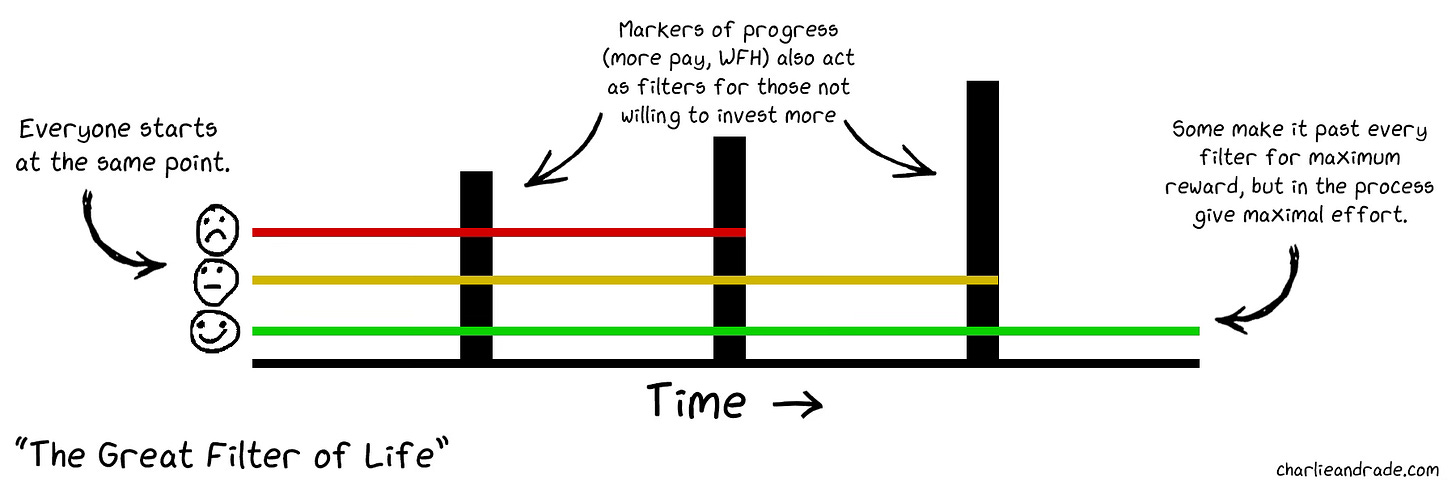

The more obvious remaining variable is intelligent life itself, which, in theory, would have to navigate intra-species conflict while sustaining a larger collective goal of cultural survival. This argument nicknamed ‘The Great Filter’, follows that at some point whether through climate chaos or species-destroying weapons, intelligent life reaches a barrier where it can, and therefore does, enable its own destruction. Where this barrier inside the filter is located changes depending on the physicist, and some argue that humanity already passed this indomitable during its initial evolution. Still, the barrier exists as an ominous warning that our species, and its destruction, may be tragically ordinary and rapidly approaching implosion.

The Fermi Paradox can apply to more than just our cosmic belonging. Life, simplified, is a series of small paradoxes where our ability to invest mental and physical energy is fought over by a multitude of responsibilities and tasks. There comes a point where the rewards from that extra hour spent at work begin to diminish, and the alternative, time spent at home with your family, offers deeper satisfaction.

For most Americans, an annual salary in excess of $100,000 brings diminishing levels of happiness. When paired with the added responsibility that more wealth demands, the tradeoff often fails to be worth it. Why, then, is this the number we seem to have settled on? Applying the Fermi Paradox to our personal lives, what is the barrier, and why does it exist, that separates high-functioning, traditionally successful individuals from those who are not?

To answer this question holistically, we need to first define the role that money plays in happiness. At first glance, the relationship would, in theory, be exponentially linear. Yet even as a surge of foreign investment has brought new economic prospects to billions of people, an associated surge in happiness has been missing. Wealth may very well provide foundational security for basic rights like housing and sustenance, but the acquisition of these necessities often feels more like a chore than a reward. Even if your income has doubled, if the doubled figure is still not enough to provide basic needs for you and your loved ones, the raise itself will fail to achieve the happiness one would expect from a 100% increase in pay. Returning to the idea of the Fermi Paradox and this ‘Great Filter’, it may be that the barrier between money and happiness rests in the ability to feed and sleep reliably and safely. Any more wealth, and the tangible emotional results are increasingly weakened to the point of invisibilty.

So, we know that money is not linearly correlated with happiness. That isn’t a novel realization, and on its own, it hardly justifies a thousand-word essay. From a young age, we’re conditioned to separate excess wealth from excess happiness—many of the foundational experiences of childhood in America involve learning this distinction. Outside the classroom, though, the power of wealth is plastered on every shoe logo and car emblem. It is both deeply woven into daily life and, at the same time, held at arm’s length—presented as central to meaning yet also as something fundamentally empty. The wealthy are imagined either enjoying pampered, leisurely lives or silently wiping their tears with Ben Franklin’s face. This creates a contradiction that hardly suits a six-year-old trying to make sense of the world: how can you not be happy with millions in the bank? That just doesn’t sound right. But it also fails to answer the deeper question—why do people keep chasing money if it so often fails to deliver the happiness they’re after? Maybe we’re misdefining happiness itself.

Money may not equal happiness, as the data shows, but it certainly equals status. Status is a feeling that only emerges once more foundational but immediate concerns are addressed. To even think about status, which is your position in relation to a larger group, you have to have the mental capacity to stop worrying about what to eat and where to sleep. Even if status is not a new human emotion, its dispersion beyond historically elite classes is worth examining. Terms like “palace intrigue” stem from the idea that interpersonal games and prestige were once luxuries reserved for a small segment of the population unburdened by physical labor or survival. Status is no longer determined by crowns and kings, but by money and the things it can buy, with more regal toys to go around.

You could argue that, for the United States at least, the barrier between money and happiness is located here. Past this point lies a structurally different world, one with new social and economic expectations that demand more from the individual. This matters because it reveals the fluidity of our relationship with money. If people were focused solely on accumulating wealth or even on visibly displaying that wealth, we would see a mass migration of young professionals to low-cost-of-living cities. Yet the opposite is happening. New York City is gaining population again, even as housing remains scarce, a trend also seen in cities like Austin and Miami. These cities compete not on cost but experience, the actual lived reality that makes higher rents and more traffic worth it. Clearly, something larger than money is at play here, a force that is shared in cities but also deeply personal and reflective of a more complex relationship with wealth.

Increasingly, the barrier we are describing can no longer be tied directly to the dollar at all. We have become desensitized to wealth and, in many cases, disgusted by its flaunting. There was a time when the glitz and glamour of a high net worth acted as a private invitation into a world that most people would never access. Now it feels like every blue checkmark is posting photos of their Gulfstream to the Hamptons. There is an argument to be made that money has always been a vessel for status and positioning, and that argument has merit. What is new, and worth discussing, is the question of where we now draw our sense of self-worth from.

The absence of something does not necessarily signal the end. Traditional workplaces are not integral structures to humanity, and the rise of generative AI and agential learning threatens a white-collar extinction event. We may live in a world without traditional work sooner than expected, but our physiological need for meaning and fulfillment will not disappear nearly as fast. In order to come out the other side of this historic shift with a recognizable species and a more equitable future, it will take real work. Will we be satisfied with some form of universal basic income? Will wealth continue to carry the same social weight? Will it carry any at all? These are questions we cannot answer now, but the act of asking them may be enough for the moment.

Even if the search for life has left us empty-handed, the search itself gave rise to the Fermi Paradox. Unlike the relatively objective criteria for identifying life beyond Earth, and the barriers that can be imagined in that context, our lives on Earth are shaped by a series of smaller Fermis and filters, each one urging us to locate our barriers, define our limits, and question whether we are anywhere near overcoming them.