To the Death

On Gary Hart and the power of hubris

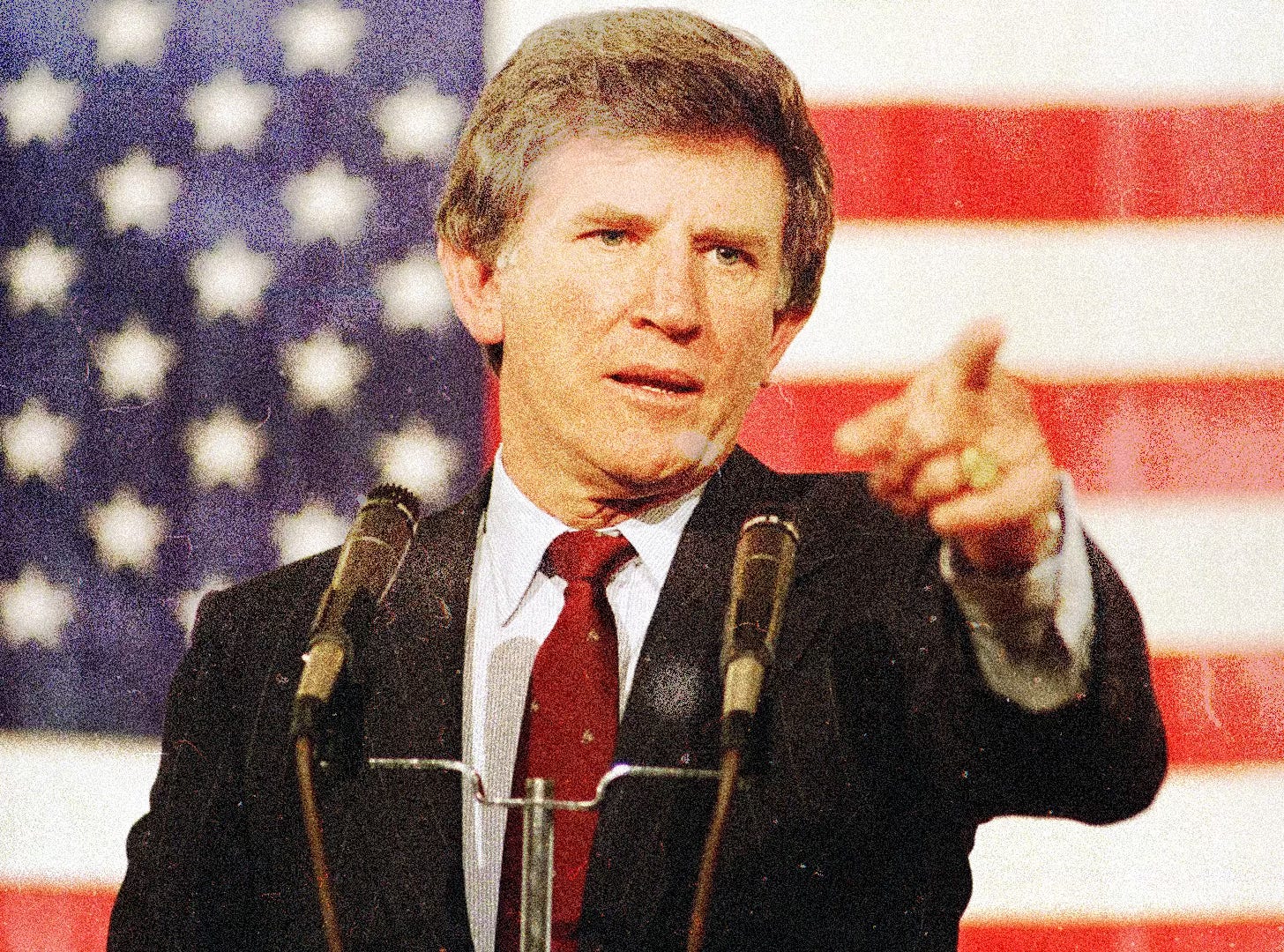

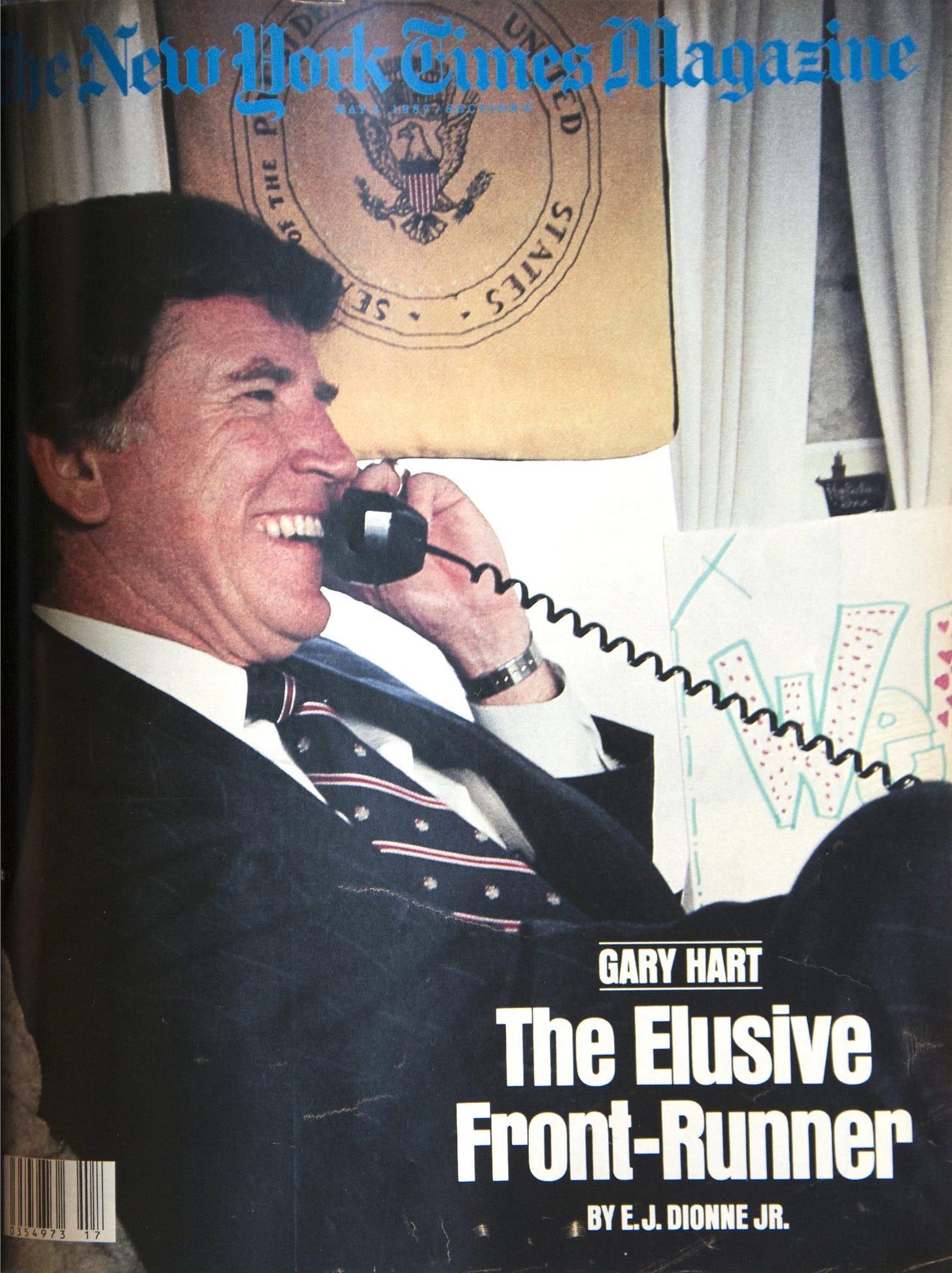

If you were to create a machine that could simulate the 1988 Democratic Presidential primary a thousand times, I would bet most of those simulations would leave you with Gary Hart as the nominee. Hart, the Democratic Senator from Colorado, the runner-up for the nomination four years before, was the clear front-runner for months leading to Iowa. His opponents, a smattering of coastal politicians like Senator Joe Biden, and Governor Michael Dukakis, seemed destined to earn their epitaph on the ever-expanding grave of “Also ran:”. The only thing stopping Hart from winning, was himself.

Gary Hart was a man who needed to be understood. Needed it more than most politicians do. For Gary Hart, running for President was a duty. A responsibility. Gary Hart would never—could never—be the cool, calm, and collected politician who could get your son a job as thanks for your work in Iowa. No. For Gary Hart, the work of the campaign—of his ideals and value—was all that should be enough. This was the Presidency. The toughest job in the world. A job so stressful that eight years of it turned a fresh-faced Barack Obama into a grizzled veteran of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. For Gary Hart to survive, he had to be himself: a man who, just by the stroke of luck, had his ambitions aligned to his morals.

It would be through character that Gary Hart would win the nomination. Grit. Honor. It should speak to Hart’s obsession with this natural statesmanship that his original campaign announcement was scheduled to take place on his porch. Hidden away in the mountains of Colorado, with TV vans adorned with the major network logos, with lumbering satellites welded onto the top, the Hart campaign for President would begin. You could also argue that this campaign was larger than just one office. It was a vision of America that Hart wanted—wished so bad to be true that he believed it was real—to see.

For years, since he made his name as the young and fashionable campaign manager of the young and fashionable McGovern 72’ campaign, Hart never could be comfortable with letting the world into his personal life. He could talk for hours about the need for diplomacy with the Soviet Union, about his plan to keep American jobs, about anything you cared about knowing. That was the “Ability” in “Elect Ability”. If you asked about his family? His backstory? Forget it. That was private—and more importantly—irrelevant. Why would that matter? Was Lee Hart, Gary’s wife, running for President? Of course not.

To a raucous media though, this resistance to opening up signaled a story. It was as if Hart was holding a ribeye over a pit of hungry lions—how could they not swipe their paws and grab it? For months the Hart campaign would be dogged by stories of a candidate that the media just could not understand. Journalists were careful to not overstep—to name directly what exactly they found so odd about Hart—but the drip of stories seeped into the foundation of an already apprehensive candidate. The media was against Gary Hart! Wanted him to not just lose, but to be battered! humiliated! The three-letter hounds wanted a reminder to all other candidates that the almighty media had a responsibility to investigate the personal lives of men who wanted the nuclear briefcase.

That’s where Hart would find his end. A story would release—one of those journalists who had badgered the campaign for the last year—accusing Hart of the cardinal sin of pre-Clinton politics: an affair. The evidence was damning: Hart with a woman many years younger on his lap. To make it better, Hart was wearing a shirt that said ‘Monkey Business Crew’. It was perfect! The media was right! Hart was hiding something—something disqualifying—and he thought he could outsmart the media. America was defended! Democracy was preserved! The checks had checked! The balances had balanced!

There’s a lot more to write about Gary Hart, and I would recommend you read the brilliant ‘What it Takes’ by Richard Cramer to learn more. For the purposes of this piece, though, I think the basic story is enough. It’s a story of a man who wanted to have it both ways. Gary Hart wanted to be President, wanted the recognition for his humbleness. He wanted—believed—that this country would see him for what he was. It wouldn’t matter that some New York journalist wanted to break the next Watergate. Americans could see! They could see why it wasn’t unreasonable to ask for a bit of privacy. Why his modest home life was just that—modest—not some cover for a darker conspiracy!

Perhaps if Hart had been more friendly with the media—more willing to play ball—that he could avoid the monkey business he became engulfed in. Perhaps Hart could’ve politely declined the photo he so eagerly posed for. It speaks to how deeply Hart believed that personal matters should stay personal that a photo like that even exists. It reflects a man whose hubris had not only grown so tall to think he could become President, but that had grown so wide that he believed he was an intractable force.

In truth, I think my fascination with the story of Gary Hart is how much he reminds me of myself. I find myself struggling with the same clash that I believe brought Gary Hart to be the frontrunner for the nomination, and then dragged him to the footnotes of history. It’s a belief in yourself that is different, I believe, than many of those who run for President. A belief that you, yourself, can will a different world into existence. A feeling, deep down past humility and humanity, that you are meant to be something bigger than one person.

Whether I admit it or not, this belief is the fuel that powers my internal engine of ambition. It’s a scary belief, because of how easily it is to be proven wrong. My standards for myself—for what I think I can achieve—are so high that I find myself worried if I have set standards that no human can meet. Can I become a Governor in my thirties? A Senator? If I don’t, will I be a failure? If I do, will I still be recognizable? I don’t know. I don’t think you can ever know until you kneel at the altar of ambition and give everything in service to it.

“Gary Hart thought-he had thought—he’d get home and, somehow, he’d go on with his life. But he was not going to have his life back.

The phrase occurred to him: to the death. He learned in the car... when he felt it rock with the impact of bodies, and a bare hand hit with a smack on his windshield, and there were people yelling and pounding on the car, with cameras in front, and he couldn’t see to drive, and Lee was beside him, fragile he thought, as he gunned the engine, trying to make them move... and he jumped when a lens with a rubber sleeve hit-THUNCK— against his window and stuck there, filming him, shooting at him, and he couldn’t see the human on the other side—but he learned... something new:

If he could have, he’d have jumped out and beaten them with his bare hands”

Hi Charlie .....

You may be too young .... but there used to be a show called "Inside the Music" a documentary style show where the life of a musician ... from beginnings, to success, to failures, and finally some ending where there were lessons learned, with some sort of humility.

Everyone in the public sphere tend to follow this rise and fall .... circle of life. The media thrives on this.

I think we all have the same theme in our private lives. I'm struggling to write/complete my autobiography .... but I see the same themes over my lifetime. Humble beginnings, then success-to-failure-to-humility.

Poor Gary Hart. The media to a microscope to his personal life. He deserved better.

We've now come full circle .... Trump, convicted rapist, and a very likely pedophile, gets elected overwhelmingly a second time. I don't get it ..... but it's clearly a consequence of a very divided country.

Scott